Detection and attribution of change in forest restoration needs in the PNW

Widespread fire suppression (early 20th century to present day) and intensive tree harvesting (19th to early 20th century) have shifted the composition and structure of many western forest landscapes beyond their historic range of variability. In dry inland forests of the PNW, novel forest conditions (e.g., abundance of high density, closed-canopy forests dominated by fire-intolerant species) have interacted with changing climate to incite rapid increases in disturbance activity. In contrast, the moister forests west of the cascade crest have been shaped by a century and a half of industrial forest management, resulting in landscape fragmentation (e.g., checkerboard patterning), simplification of forest structure (e.g., predominance of early and mid-seral plantation settings, lack of coarse wood), and loss of late-seral conditions across a broad spatial domain. While patterns of change differ strongly between dry and moist forests of the PNW, reversion of landscape composition (e.g., relative abundance of community types), structure (e.g., seral-stage distributions), and function (e.g., fire regimes, nutrient cycling) towards historically ``stable” conditions is broadly assumed to increase forest resilience to future changes in disturbance regimes and environmental drivers. As such, agencies tasked with managing public forestland in the western US have broadly adopted principles of ecological restoration and landscape-scale management, and face the immense challenge of increasing the pace and scale of forest restoration in the midst of changing disturbance regimes, climate, and societal values.

Previous studies have sought to support forest restoration efforts by quantifying structural restoration needs and determining where, how much, and what forms of treatment are required to shift the structure of present-day forest landscapes to meet historically “stable” conditions across the PNW. However, these studies have been unable to quantify the uncertainty associated with their estimates of restoration need, nor the the accuracy of their approach in characterizing current vegetation at broad spatial scales. In the context of decision-making, proper quantification of uncertainty (e.g., in the form of confidence/credible intervals) is often as important as point estimation; the range of credible estimates of forest restoration need is of no less value than our “best” estimate and should be quantified whenever possible. Further, previous studies have aimed to characterize forest restoration needs at single points in time, and thus have not provided a mechanism to detect statistically significant change in restoration needs or quantify the relative importance of disturbance and successional processes in driving such change. It is reasonable to expect that the composition and structure of forested landscapes have changed considerably over recent decades in the PNW, in light of increased wildfire activity and recent outbreaks of native insects in the region. In many cases, disturbances may contribute to forest restoration objectives directly (e.g., “restoration wildfire” in the dry domain), and as such, quantifying the patterns and underlying drivers of change in forest structural restoration need is a key challenge for ecological research.

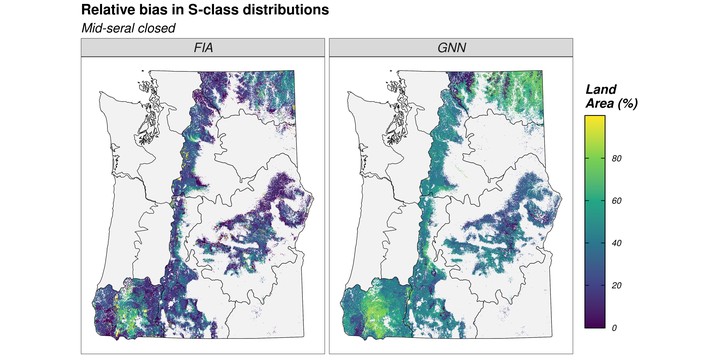

Here, we propose a re-evaluation of forest structural restoration needs in the PNW under a design-based setting (i.e., as opposed to a model-based as used previously). Specifically, we seek to (1) generate unbiased, annual estimates of forest structural stage distributions and associated uncertainty using the FIA Database over the period 2002-2019; (2) compare design-based (i.e., FIA) and model-based (i.e, GNN) estimates of restoration need to determine the “accuracy” of model-based summaries; (3) draw on remeasured FIA plots to derive an estimator of average annual change in forest restoration need over the last two decades in the PNW.

Research Questions

Do design-based and model-based estimates of restoration need differ in a systematic manner?

- Does the magnitude of divergence in restoration need predicted under each paradigm vary across space and/or by type of treatment needed?

- What stand structural stages are primarily responsible for driving divergence in restoration need, and what does this indicate about prediction uncertainty of the model-based estimator

- At what spatial scales do estimates of structural stage distributions and/or restoration needs diverge, if ever?

How have forest structural restoration needs changed over the last 20 years in the Pacific Northwest?

- How have natural disturbances (i.e., fire, insect outbreaks, disease, and wind), silvicultural treatments, and succession to contributed to such change?

- When, where, and to what degree have natural disturbances and succession contributed directly to forest restoration objectives, and what does this indicate about optimizing the impact of limited resources for silvicultural intervention?

Approach

Since 1999 FIA has operated an extensive nationally-consistent forest inventory designed to monitor changes in forests across all lands in the US. The program measures forest variables on a network of permanent ground plots that are systematically distributed at a rate of approximately 1 plot per 2428 hectares across the US. In Oregon and Washington, sampling has been intensified on some lands (i.e., primarly national forests), often yielding estimators with higher precision within small domains (i.e., small spatial domains and/or rare forest attributes) relative to other states. Importantly, ground plots are remeasured every 10-years in the western US, and approximately 14,000 forested plots have been remeasured in Oregon and Washington to date.

Using the FIA plot network, we derive a design-based estimator of forest structural stage distributions (and subsequently restoration need) that is directly comparable to the model-based estimator used by and DeMeo et al., 2015. First, we classify FIA plots into one of five mutually exclusive structural classes using on an algorithm first presented in Huago et al., 2015. We then apply post-stratified estimators implemented in the rFIA R package to estimate total and proportion forest land area within each structural classes along with associated measures of uncertainty (i.e., variance of the estimator). Treating reference conditions as known values, we then apply a “restoration needs” algorithm described in Huago et al., 2015 to estimate total restoration need within classified domains (e.g., HUC units, ownership types, etc). The purpose of this “restoration needs” algorithm is to shift land area from over-represented structural classes (relative to historic conditions) to under-represented classes. Importantly, these shifts do not affect the variance of the estimator of total forest land area as we are simply adding/subtracting scalars in each case. That is, the variance of the estimator of total forest restoration need is exactly equal to that of the estimator of total forest land area using this approach, as reference conditions are not treated as random variables but as fixed, known boundaries.

Similarly, we derive an estimator of average annual change in forest restoration need by redefining FIA’s current area inventories to include only remeasured plots. In short, this allows us to estimate structural stage distributions at two points in time using an identical sample of FIA plots, and hence estimate temporal change in forest restoration need. Further, we can directly attribute changes in structural stage distributions to natural forest disturbances, silvicultural treatments, and succession (transition in structural class in the absence of disturbance/treatment) using disturbance codes collected by FIA field crews. Estimated change in structural stage distributions arising from such processes can then be used in our “restoration needs” algorithm to determine the degree to which natural disturbance, silvicultural treatment, and succession have contributed to restoration objectives within classified domains.